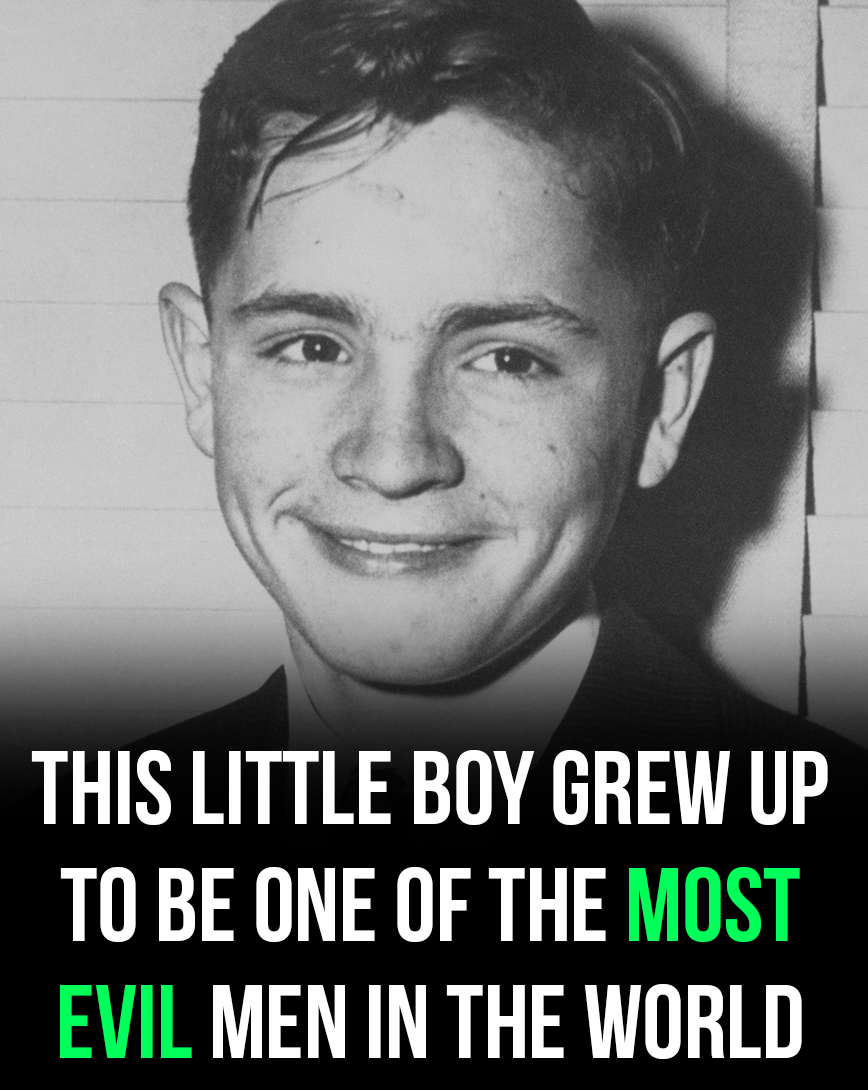

This Harmless-Looking Boy Grew Up to Be One of the Most Evil Men in History

There exists a photograph taken in the late nineteenth century: a small boy with a round face, neatly combed hair, and wide, untroubled eyes. He looks ordinary—sweet, even. There is nothing in his expression that hints at cruelty, hatred, or violence. He could be anyone’s child: a neighbor’s son, a classmate, a quiet boy sitting in the corner of a schoolroom.

Few images are as unsettling as childhood photographs of history’s most infamous figures. They force us to confront an uncomfortable truth: monsters are not born looking like monsters. They begin life as children—vulnerable, impressionable, shaped by their surroundings. Hitler’s transformation from an unremarkable Austrian boy into the architect of genocide and global war is one of the most disturbing moral collapses in human history.

Understanding how this happened does not excuse his crimes. But refusing to understand it risks repeating history.

This is not just the story of one man. It is the story of how ideology, trauma, grievance, and power can twist an individual—and how society can enable unimaginable evil.

A Childhood That Looked Ordinary from the Outside

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, in Braunau am Inn, a small town in Austria-Hungary. His early life appeared largely unremarkable. He was the fourth of six children born to Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl. Only Adolf and his younger sister Paula survived into adulthood, a fact that would quietly shape his emotional world.

His mother, Klara, adored him. By many accounts, she was gentle, attentive, and deeply protective. Hitler later spoke of her with rare affection, describing her as the only person he ever truly loved. This maternal devotion likely gave him a sense of emotional centrality—being special, chosen, and deserving of attention.

His father, Alois, was the opposite.

Alois Hitler was authoritarian, volatile, and physically abusive. He demanded obedience and had little patience for weakness or dissent. Young Adolf clashed with him repeatedly, especially over career ambitions. Alois wanted his son to become a civil servant; Adolf dreamed of being an artist.

Early Signs of Alienation and Fantasy

As a child, Hitler was not notably cruel or violent, but he was already retreating inward. He struggled socially, performed unevenly in school, and developed a tendency to escape into fantasy. He loved heroic myths, German nationalism, and grand historical narratives filled with struggle and destiny.

This mattered.

Fantasy can inspire creativity—but when combined with frustration, humiliation, and entitlement, it can become dangerous. Hitler increasingly imagined himself as someone meant for greatness, unfairly held back by forces he did not yet fully understand.

When his father died in 1903, the household power structure collapsed. Adolf was suddenly freer—but also unmoored. His academic performance worsened. He failed to complete secondary school. His dreams of artistic success would soon meet brutal reality.

The Crushing Weight of Failure

At age 18, Hitler moved to Vienna, convinced he would be accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts. He was rejected. Twice.

Vienna was also where Hitler’s worldview began to rot.

Continue reading…