The city was a melting pot of ethnicities, religions, and political movements. Instead of broadening his perspective, this diversity fueled his growing paranoia. He absorbed antisemitic propaganda, racial pseudoscience, and nationalist rhetoric. These ideas gave him something intoxicating: enemies to blame.

Failure became persecution. Disappointment became injustice.

Poverty, Rage, and Radicalization

Between 1909 and 1913, Hitler lived in near homelessness. He slept in shelters, sold postcards for money, and existed on the fringes of society. This period is crucial—not because it excuses his later actions, but because it hardened his worldview.

He saw himself as superior yet humiliated.

Destined for greatness yet trapped in obscurity.

Pure yet surrounded by “corruption.”

This is a dangerous psychological cocktail.

Rather than fostering empathy for the poor, Hitler’s poverty deepened his contempt for weakness. He began dividing the world into rigid categories: strong vs. weak, worthy vs. unworthy, us vs. them. His thinking became absolutist, paranoid, and increasingly violent in its logic.

What he lacked in power, he compensated for in ideology.

War as a Turning Point

When World War I broke out, Hitler found something he had been missing his entire life: purpose.

The experience also traumatized him.

He witnessed mass death, destruction, and suffering. But instead of processing this trauma with grief or humility, he absorbed it as fuel for rage. When Germany lost the war, Hitler did not see defeat as a consequence of strategic failure or exhaustion. He saw betrayal.

This belief—that Germany had been “stabbed in the back” by internal enemies—became central to his ideology. It allowed him to preserve his self-image while redirecting blame outward.

Reality bent to his need for meaning.

From Nobody to Demagogue

After the war, Germany was in chaos. Economic collapse, political extremism, and national humiliation created fertile ground for radical voices. Hitler, once a drifting failure, discovered a terrifying talent: public speaking.

He could mesmerize crowds.

Crucially, he learned to perform hatred as virtue.

By the early 1920s, he had become the face of a growing political movement. The harmless-looking boy had become a man who thrived on rage, applause, and dominance.

Power Without Restraint

Once in power, Hitler’s worst traits metastasized.

His inability to tolerate dissent became tyranny.

His need for admiration became cult worship.

His obsession with purity became genocide.

The Holocaust was not an accident. It was the logical conclusion of decades of dehumanization, propaganda, and ideological obsession. Millions were murdered not in moments of passion, but through bureaucratic efficiency.

What makes this especially chilling is how many people participated.

Evil, in this case, was not just personal—it was systemic.

The Myth of the “Monster”

It is tempting to view Hitler as inhuman, as a singular embodiment of evil. But this temptation is dangerous. When we label him a monster, we distance ourselves from the conditions that made him possible.

Hitler was human.

He was shaped by family, failure, trauma, and society.

He was enabled by fear, silence, and complicity.

This does not diminish his guilt—it magnifies our responsibility.

Because the truth is: history does not repeat itself through identical figures. It repeats through familiar patterns.

Why This Story Still Matters

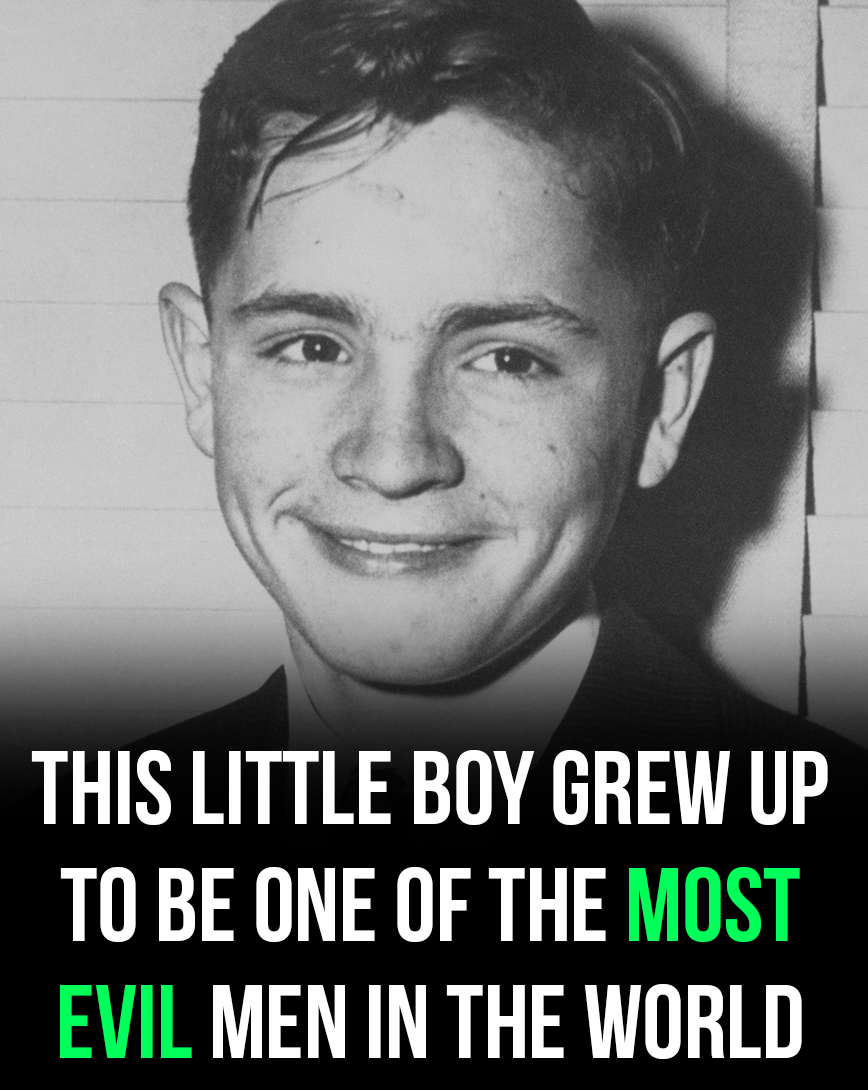

The photograph of that harmless-looking boy unsettles us because it reminds us that evil does not announce itself clearly. It grows quietly—through grievance, radicalization, and unchecked power.

Hatred often begins as wounded pride.

Violence often begins as rhetoric.

Atrocity often begins as an idea.

Studying Hitler’s life is not about fascination—it is about prevention. It forces us to ask hard questions about how societies treat failure, how leaders exploit fear, and how easily humanity can be stripped from “the other.”

Conclusion: The Warning in the Photograph

That childhood photograph should not horrify us because the boy looks evil.

It should horrify us because he doesn’t.

It reminds us that vigilance matters. That empathy without accountability is not enough. That ideas have consequences. And that the line between ordinary and monstrous is thinner than we like to believe.

History’s greatest horrors did not begin with fire and blood.

They began with a boy who felt wronged by the world—and a world that failed to stop him.