School was especially difficult. While other children worried about homework or playground games, Terry had to navigate social isolation, bullying, and the constant awareness of his scars. Teachers often didn’t know how to handle him—how much to protect him, how much to treat him “normally.” Well-meaning adults sometimes lowered expectations, assuming that someone who had suffered so much physically could not handle emotional or intellectual challenges. These assumptions, though often subtle, could be just as damaging as outright cruelty.

His family played a crucial role in this process. Caring for a severely burned child is emotionally and physically exhausting. The constant hospital visits, the financial strain, the fear of losing him, and the helplessness of watching someone you love suffer can tear families apart. That Terry continued to fight suggests that somewhere around him was support—people who believed his life was worth fighting for, even when the road ahead seemed endless. Love, in such circumstances, is not abstract; it is practical, persistent, and often painful.

As Terry entered adolescence, new challenges emerged. Puberty is difficult for anyone, but for someone with extensive burn scars, it can feel unbearable. The desire to fit in, to be attractive, to be accepted clashes violently with a body that draws attention and judgment. Romantic relationships, or even the hope of them, can feel out of reach. Rejection—real or anticipated—can lead to isolation, anger, or deep self-doubt. Terry had to learn not only how to live in his body, but how to believe that his body did not disqualify him from love, friendship, or dignity.

The surgeries continued into adulthood. Burn injuries do not simply “heal” and disappear; they evolve. Scar tissue does not grow like normal skin, so as Terry’s body changed, new medical interventions were required. Each operation reopened old wounds, both physically and emotionally. The smell of antiseptic, the sterile lights of operating rooms, the vulnerability of anesthesia—these experiences became recurring chapters in his life story. For many people, trauma fades with time. For Terry, it was revisited again and again.

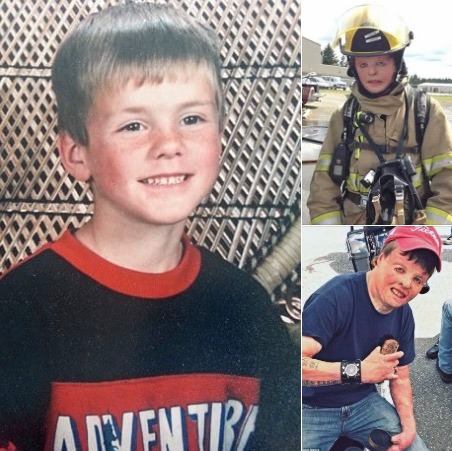

And yet, within this cycle of suffering, Terry found ways to reclaim agency. Over time, he learned that while he could not control what had happened to him, he could influence how he responded to it. This shift in perspective did not erase pain or hardship, but it transformed them. Instead of being defined solely as a victim of a horrific accident, Terry began to see himself as a survivor—someone who had endured what many would not, and who was still standing.

Living with severe burn scars also forces a confrontation with society’s values. Terry’s life exposed the uncomfortable truth that people often equate physical appearance with worth. He experienced firsthand how quickly assumptions are made, how easily people reduce others to what they see on the surface. Over time, this awareness sharpened his empathy. He understood what it meant to be judged before being known. That understanding, hard-earned through suffering, became one of his greatest strengths.

There were undoubtedly moments when despair threatened to overwhelm him. Chronic pain, repeated surgeries, social rejection, and the sheer exhaustion of always having to be “strong” can wear anyone down. Strength is often romanticized, but in reality it can be lonely. People praise resilience without acknowledging the cost of constantly needing it. Terry’s journey was not one of unbroken courage; it was likely filled with fear, anger, grief, and exhaustion. What makes his story remarkable is not that he never struggled, but that he continued despite those struggles.

As an adult, Terry carried his scars into every room he entered. They announced his presence before he spoke, shaped first impressions, and sometimes closed doors. But they also told a story—a story of survival, endurance, and an unwillingness to surrender to tragedy. Over time, Terry learned that while he could not escape his past, he could decide how much power it held over his future.

His life stands as a quiet challenge to simplistic narratives about suffering. Trauma does not automatically make someone noble or wise, nor does survival guarantee happiness. What it can do, however, is reveal the depths of human endurance. Terry McCarthy’s life illustrates that resilience is not a single heroic moment but a series of choices made under unbearable pressure. It is waking up one more day. It is agreeing to one more surgery. It is choosing to believe, again and again, that life is still worth living.

And yet, Terry is more than what happened to him at six years old. He is more than his injuries, more than the operations, more than the stares and whispers. His identity cannot be reduced to a moment of violence or a lifetime of medical procedures. He is a person who endured unimaginable pain and continued forward, carrying both wounds and wisdom.

In the end, Terry McCarthy’s story is not simply about tragedy—it is about persistence. It is about the human capacity to adapt to circumstances that seem impossible to bear. It is about the long, unglamorous work of survival, carried out day after day, year after year. And it is a reminder that behind every scar is a story far deeper than what the eye can see.